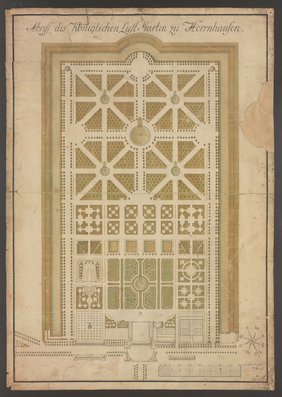

In the spring of 2024, during repositioning work in the stacks of the TIB/University Archive in Hannover-Rethen, a TIB employee accidentally came across a series of historical drawings and prints that had not been inventoried, including a large-format sheet with a plan of the Great Garden of Herrenhausen. It soon emerged that the majority of the sheets originally belonged to the holdings of individual prints from the Albrecht Haupt Collection. The discovery of the plan was a particularly pleasant surprise, as the plan, which dates back to 1777, had been considered lost since the Second World War. In his catalogue of hand drawings from 1899, written in his own hand, Haupt had listed it under the keyword "Garten-Anlagen" as "Abriss des Königlichen Lustgartens zu Herrenhausen. 1777. G.F.K." and marked it as particularly valuable. The art historian Lieselotte Vossnack, who had been entrusted with the collection since the late 1930s, also devoted a short paragraph to the plan in an expert report on the collection written in 1941. "A lucky coincidence", she wrote there, "played into Albrecht Haupt's hands one of those plans of the Great Garden in Hannover-Herrenhausen (with the exception of minor alterations in the early 18th century, a repetition of the plan from Hannover-Herrenhausen). It is a repetition of Charbonnier's plan, according to which the garden was given its present form) dated 1777, a year in which the idea of transforming the entirely architectural garden into an English-style park was being considered."

As is well known, these plans were never realised due to a lack of interest on the part of the Guelph dynasty ruling in London, so the garden largely retained its baroque structure over the following decades. This can essentially be traced back to the plans of the court gardener Martin Charbonnier, who was entrusted with the garden from 1683, and his son Ernst August Charbonnier, who succeeded him in office. Under their direction, the garden laid out in the late 1660s was restructured and significantly extended in several phases up until the 1720s.

Based on the mentions in Haupt and Vossnack, one might assume that the plan must have been well known to older researchers, but it was not mentioned in the relevant literature on Herrenhausen and was also not included in the large anniversary exhibition on the Great Garden organised by Lieselotte Vossnack herself in 1966. The plan also came as a surprise to Bernd Adam, a recognised expert on the planning and building history of the Herrenhausen gardens. "In detail," says Adam, "for example with regard to the internal division of the planting west of the grotto, it deviates from all plans that I am aware of. The aforementioned planting next to the grotto showed a different layout in 1773 and thus close in time to the dating of the newly developed plan, according to a ground plan sketch of the grotto and fig garden by Johann Dietrich Heumann [...], which also appears several times in older plans."

These include the "Plan Generale de la nouvelle Machine, Écluse, et du Canal, comme aussi du Jardin et des Batiments de la Cour à Herrenhaussen" by Anton Wilhelm Horst from the so-called "Mecklenburgische Planschatz", which has only been known to experts for a few years and was probably created in the early 1740s. A comparison with this plan reveals further differences, which are presumably due to schematic simplifications, for example in the garden theatre or the bosquets in the main axis in front of the large fountain, which are shown as wooded areas in the 1777 plan. The areas of the two garden sections directly adjoining the palace, the flower garden and the fig garden behind the grotto, already mentioned by Adam, were strangely left empty, while the garden for melons and fruit to the north of the fig garden also shows empty areas as well as a different basic structure. The plan is thus reminiscent of older depictions such as the plan of the gardens by Pierre Nicolas Landersheimer from around 1720. What the latter also has in common is that the geometry of the garden is idealised, i.e. without the actual slight distortions of the entire complex. At the same time, the plan seems to document the decline of the areas originally planted with ornamental plants, which could no longer be maintained at the end of the 18th century.

Adam surmises that this could have been a drawing exercise. As early as the 1720s, court servants were required to make copies of plans from the plan chamber. The fact that the plan, unlike the other known plans, was drawn without an explanatory legend and that the draughtsman's monogram has not yet been linked to any building servants or copyists from this period also speaks in favour of a study or practice sheet. There is therefore still a need for further research. It is therefore all the more welcome that this valuable testimony to the history of the Great Garden in Herrenhausen has now returned to the collection and is accessible via our SAH-digital portal.

Simon Paulus